Matteo Peraldo

New York

Aerospace never really learned the concept of just in time. Despite all the efforts of A&D companies to implement Kanban and pull methodologies, the results were lagging compared to automotive and other industries.

But with interest rates rising globally, and cash requirements increasing due to the current big production ramp-up, improving inventory performance needs to become a priority. The return on investment for inventory reduction initiatives can be very high – but moving fast is important.

Why is aerospace inventory turnover much lower than automotive, consumer goods, and most other industries? A look at manufacturing footprints and logistics flows helps explain why.

In the case of automotive, for instance, suppliers tend to reside close to OEM plants, so finished goods are minutes away from the customer. Compare that to the Boeing 787 program as an example, where many key suppliers are several time-zones or even an ocean away. The wings are built in Japan, fuselage in Italy, final assembly is done in South Carolina. This setup is the result of the “risk-sharing partners” model introduced with the program, but it does not optimize logistic flows and working capital. The 787 may be an extreme case, but virtually every aerospace program has major components from different countries.

The “missing parts” phenomenon is another challenge somewhat unique to aerospace. Due to a mix of mediocre supply chain performance (on-time delivery often below 90%), recurring quality issues, and late modifications, every aircraft produced suffers from several parts arriving late and being fitted outside the nominal process. As a result, aerospace players have traditionally added buffers to their orders to the supply chain to minimize missing parts and protect production -- a move that is prudent but not helpful to working capital.

While logistics and supply chain are far from optimized, the main reason for the low inventory turnover in aerospace is Work-in-Process (WIP) inventory. For aircraft OEMs, for instance, we estimate that roughly 70% of the total inventory is trapped in the Final Assembly Line WIP. Aerospace manufacturing lead times are much longer than most other industries, and this is the biggest driver for inventory. It is also the greatest target for improvement.

Emerging from the pandemic, inventory turns in the industry are deteriorating. This is due to a combination of factors:

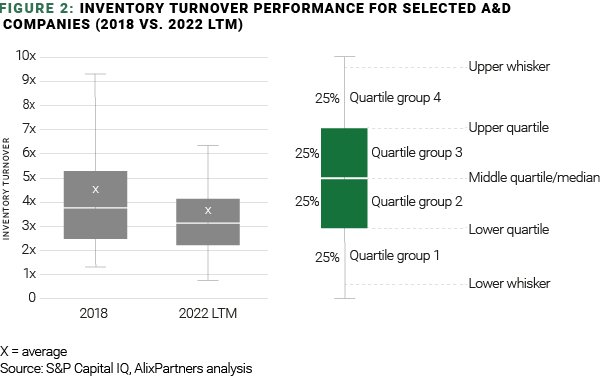

On average, inventory turnover performance for A&D companies significantly deteriorated during and following the 737MAX and COVID-19 crises. But while the top quartile performers managed to limit the decline to 9 percentage points between 2018 and 2022 LTM; the bottom quartile performers saw their turns go down by almost 30 points. This is evidence that while a few leading players worked diligently to offset the impact on inventory at least partially – they are the exception. Too many overlooked inventory performances and are now struggling to bring turns back to pre-COVID levels.

In absolute value, in 2022 LTM, the median inventory turnover for the sample of selected A&D companies was 3.2x, down from 3.7x in 2018. Before the crises, top quartile performers were achieving inventory turns above 5.2x; now a performance above 4.1x would put you among the best in class. On the other hand, performance for the bottom quartile is relatively stable, with 2.5x in 2018 vs. 2.3x in the last twelve months.

Interest rates have skyrocketed, making financing more complex and expensive for aerospace companies. For example, in what is about to become a common trend, Spirit AeroSystems recently successfully raised $900 million in debt, but at a rate significantly higher than the outstanding notes. Spirit AeroSystems is a large and stable company; for smaller or more leveraged suppliers, fundraising will be even more difficult.

In this context, inventory reduction – once a nice-to-do – needs to become a top item on the agenda of aerospace leaders looking for effective ways to free up cash. But beware: Most inventory reduction playbooks and popular methods will not work for aerospace in the current environment. In fact, they might make things worse.

Based on our experience in optimizing the working capital in A&D, and the work we are currently doing with small and large players in the value chain, pulling the following levers should be part of every aerospace inventory reduction program:

While high inventories in a world when interest rates were low might have been a forgivable sin, unlocking the cash needlessly bottled up in inventory could make a difference in a recession. The return of investment for inventory reduction initiatives has never been so high. Sitting still will be a costly strategy.

A thorough analysis of where you sit among your competitive set, followed by an expedient and customized action plan, can prepare your company for any upcoming economic storms.

Eric Bernardini

Managing Director

[email protected]

Pascal Fabre

Managing Director

[email protected]

Notes

Note 1: Inventory turnover calculated as Operational Inventory (Raw Material, WIP, Finished Goods) on COGS

Note 2: Sample of A&D companies includes Kratos Defense & Security Solutions, Inc., Ducommun Incorporated, Aerojet Rocketdyne Holdings, Inc., Barnes Group Inc., HEICO Corporation, Moog Inc., Triumph Group, Inc., Hexcel Corporation, Kennametal Inc., Airbus SE, AMETEK, Inc., Astronics Corporation, ATI Inc., The Boeing Company, Bombardier Inc., CIRCOR International, Inc., CPI Aerostructures, Inc., Crane Holdings, Co., Curtiss-Wright Corporation, Eaton Corporation plc, FACC AG, General Electric Company, Héroux-Devtek Inc., Honeywell International Inc., Howmet Aerospace Inc., Innovative Solutions and Support, Inc., Kaman Corporation, Latécoère S.A., Lisi S.A., Magellan Aerospace Corporation, Parker-Hannifin Corporation, RBC Bearings Incorporated, Rolls-Royce Holdings plc, Safran SA, Senior plc, SIFCO Industries, Inc., Spirit AeroSystems Holdings, Inc., Teledyne Technologies Incorporated, Textron Inc., The Timken Company, TransDigm Group Incorporated, Woodward, Inc.