Jason McDannold

Chicago

The verdict is in: Change is good, especially when it comes to product portfolios. When faced with ever-evolving markets, well-managed companies often shape and reshape their portfolios; they add or cut products and services; and they acquire or divest lines of business or whole divisions. Seeding here, pruning there, harvesting elsewhere, they act in response to market conditions, innovations, shifts in customer behaviors, and changes in profitability; and they make adjustments to business strategy.

Whatever the reason—tactics or strategies, optimizing or restructuring—portfolio rationalization has never been more important. Today cyclical and structural forces have combined to make the benefits of portfolio rationalization greater and the consequences of inaction more severe.

Inertia is not an option. It destroys not just current profitability but also future flexibility: the chance to move your chips to different squares to protect profit now—and to anticipate an upturn. When the time comes to pivot to growth, you don’t want to start the race with extra baggage in your portfolio.

Companies take one of two distinct approaches to rationalizing product and business portfolios: the external, more-complex methods of approach—such as corporate carve-outs, which provide a means to generate cash by selling off a division or subsidiary—and the internal, faster strategies like product and market consolidation and repositioning. Each one has advantages, and each carries risks. (See sidebar, Carve-out or Rationalization?) Careful consideration of benefits and challenges is essential before implementing either strategy.

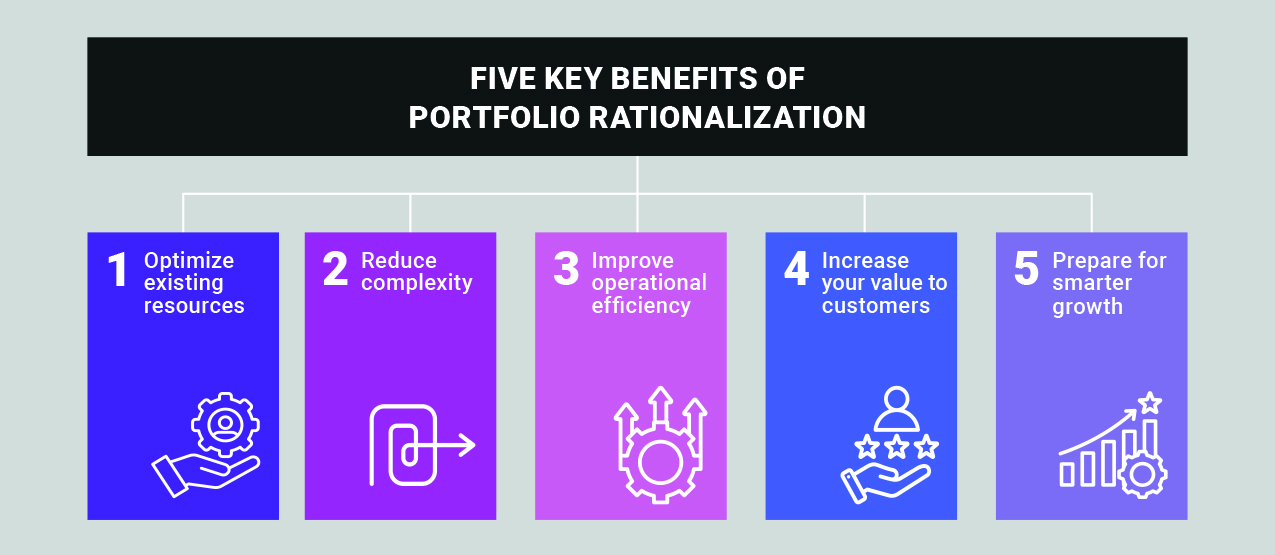

When it’s done right, rationalization in a sluggish economy can deliver five benefits—each significant in its own right, and even more powerful when they work together.

1. Optimize existing resources

Eliminating or shrinking underperforming, non-core, and non-essential products and services enables corporations to devote their resources to the most-productive, most-profitable, and most-promising areas. It amounts to a defensive move because the company’s weakest businesses will suffer most in a storm. At the same time, it is an offensive move, because it enables the company to move resources to where they will do the most good, which will keep the company ahead of the competition. Nestlé, for instance, has made product rationalization a strategic priority by focusing on brands, segments, and geographies. That focus includes withdrawing from an unprofitable Canadian frozen food market, discontinuing the Lean Cuisine frozen meal line, and selling the U.S. confectionery business to Ferrero. But Nestlé is not only cutting: simultaneously, Nestlé plans to invest $2 billion in its coffee business to enhance production capacity and develop new products, with the aim of creating a more-focused and more-profitable business there. Programs like that benefit all three financial statements—cash flow, profit and loss, and balance sheet—because the company closes cash drains, increases margins, and puts capital to better use.

2. Reduce complexity

The benefits of reduced complexity are more than financial. A complex portfolio makes decision-making difficult because it puts too many cooks in the kitchen. Portfolio rationalization simplifies both the mathematics and the politics of decision-making, resulting in a more manageable set of options and better executive alignment when it comes to making decisions about hiring, advertising, innovation, capital spending, and more. Portfolio rationalization can also enable companies to streamline and centralize certain activities. For example, AlixPartners recently supported a medical device company in pulling one of the company’s business units from barely profitable international markets. The decision enabled the company to simplify its go-to-market structure by combining the sales teams of two product groups that now have similar customer call points—an organizational benefit that added to the gain realized from exiting a no-profit zone.

3. Improve operational efficiency

Fragmented portfolios cause operational inefficiencies in the forms of high production costs, lengthy lead times, complicated supply chains, and higher general and administrative (G&A) and coordination costs, all of which can be improved by stock-keeping-unit (SKU) rationalization, supplier consolidation, and process standardization. Improvement in inefficiencies is critical during challenging economic times because companies must operate with leaner processes to generate and preserve cash. Efficiency gains depend on smart, skillful, surgical rationalization, as we will discuss below, because if a company simply cuts a SKU here or a product line there, efficiency can actually suffer.

4. Increase the company’s value to customers

When a company reshapes its portfolio to offer a coherent product mix or to serve a well-defined set of buyers, it gains several benefits with customers: First, the value proposition becomes easier to articulate. Then branding, messaging, and differentiation become sharper, which improves marketing effectiveness. And as a result, customers understand the company better. In short, the company becomes easier to do business with—which can increase sales, lower customer acquisition costs, reduce churn, and lead the company to a focus on customer success. Customer focus can be one of the most powerful benefits of rationalization, because it puts the company in a position to win on both the top and bottom lines simultaneously—in bad times or in good.

5. Prepare for smarter growth

Indeed, optimizing existing resources is a necessary first step in honing a competitive edge that leads to wins in good times, too. To create that two-edged blade, the actions you take in a downturn must pass three tests: First, they should serve to improve strategic alignment and should focus on core businesses or capabilities. Second, they should lead to more-efficient capital allocation, which will not only have immediate benefit but will also make it easier to pivot to growth by eliminating the temptation to spread growth investments around. Third, rationalization should increase agility so that the company can react faster to trouble or more quickly take advantage of new opportunities in a market undergoing constant changes. Company actions should make decision-making better, too; actions should make strategic priorities more evident to everyone; and they shouldn’t produce clutter in the form of left-behind, isolated units that require undue attention because they have no natural home. Company actions should also drive stakes into the organizational vampires every company seems to have—products or businesses whose appetite for resources leaves the rest of the company anemic and weak.

Portfolio rationalization can deliver quick improvements in cash generation and EBITDA but there’s a danger that the pursuit of fast results could damage future prospects, thereby weakening the company rather than grounding it more firmly in its strengths. Even in the toughest circumstances—like a turnaround or a restructuring—portfolio rationalization has to be accomplished with a long-term perspective. Without a North Star to guide them, companies could inflict permanent damage on themselves. They are also likely to miss big opportunities for rationalization while in hasty pursuit of small ones.

Among the mistakes we commonly see, four stand out. The first two come about when companies rationalize purely by looking at details (read, financial) but not the big picture.

1. loss of tribal knowledge of the company through tenured-employee layoffs

2. a decline in employee engagement and morale

3. lower levels of flexibility in agility when the economy bounces back

4. large, stranded costs. It may be tempting to spread the pain when making cuts in cost centers, but it’s usually a mistake.

The biggest challenge in portfolio rationalization is the need to maintain a clear perspective about timelines on one hand and levels of analysis on the other. Four views have to come into focus at the same time: today’s needs, tomorrow’s opportunities, the details, and the big picture.

1. Emphasize customer-perceived value

It is critical to bring a customer’s perspective, backed by data, into discussions of portfolio rationalization. Customer-perceived value—that is, what customers say about the benefits they get from your products and services—is too often an afterthought when teams are pursuing cash at all costs. To keep customers in the picture, think of portfolio rationalization as an exercise in design: How would you design a more profitable portfolio of offerings based on your insights about customers’ value drivers, purchase and usage patterns, and competitive benchmarks? Thinking about such design helps portfolio teams eliminate, optimize, or introduce product packages. Customer-perceived value should also drive pricing strategy by leading to an understanding of price sensitivity, alignment of pricing by customer segment, charging of premiums for the right features, quantification of the risk of customer churn, and making better decisions about the timings of price changes. By bringing a customer perspective in early, the tools of customer relationship management (CRM)—such as sales, marketing, and loyalty program messaging—become in sync with what’s changing. CRM-driven campaigns, rapid trigger surveys, and other feedback mechanisms can help avoid costly mistakes and point the company toward actions that hadn’t been considered.

2. Use the latest business intelligence tools to sharpen your decisions

By leveraging machine-learning algorithms, companies can identify patterns, trends, and correlations in their data, thereby helping them make data-driven decisions and optimize their business processes. Data analytics can dramatically improve analysis of the profitability of SKUs and product lines, parts costs, supplier costs, and the like. AlixPartners’ Global Trade OptimizerTM, which enables companies to manage supply chain disruptions in real time, can also reveal hidden sources of costs—or, better, savings. By combining such tools with predictive analytics, winning companies can identify and anticipate market trends and customer behavior. They can also model the performances of different product portfolios, optimize inventory management, and develop targeted marketing campaigns. AI can also serve to accelerate innovation—by enabling a company to turn today’s shorter product life cycle from a threat into a competitive weapon to wield.

3. Aim for progress over perfection

This is no time for analysis paralysis. Though AI and other tools have vastly increased the amount of data and the speed with which data can be understood, perfect data is unattainable. Don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good and embrace the concept of failing fast to learn and iterate quickly. The 80-20 rule is your friend—especially when it is applied by a team with deep industry expertise and a senior perspective. Align on key assumptions such as competitive dynamics, the macro environment, and customer trends. And then act.

PepsiCo sold its Tropicana juice business to French private-equity firm PAI. Johnson & Johnson (J&J) has just completed the spin-off of its consumer products business into a new public company, Kenvue. And AT&T has carved out Warner Media and DirecTV to focus on its core telecommunications business.

The three represent two distinct rationalization approaches: external, more-complex methods, such as corporate carve-outs, and internal, faster strategies like product and market consolidation and repositioning. Both offer valuable ways companies can improve profitability, concentrate on core businesses, or reduce costs. Each has its advantages.

In the first half of 2023, carve-outs accounted for 21% (2,390) of the year’s 11,313 M&A deals, and divestitures represented 16% (1,769). The numbers mark significant increases compared with 2022, when carve-outs accounted for 16% and divestitures for 14% of M&A deals.

A prerequisite for a carve-out is that a business unit can be separated—that it has a raison d’être as a stand-alone and would be big enough to attract potential buyers or investors—and when operations can be separated without too much pain and without leaving one company or the other lacking essential capabilities. Carve-outs are particularly attractive when the market values one kind of company differ from those of another—for example J&J’s separation of its pharmaceutical and consumer products businesses—or when market segments are distinct—for example, Corteva, created to own the agriculture businesses that had been part of the Dow and DuPont chemical family.

Carve-outs can yield significant benefits. They provide a means to generate cash by selling a company division or subsidiary. Often, the original company retains an equity stake in the carve-out, which, if the new entity fulfills its promise, can generate additional, ongoing value for the originating company. And the carved-out entity is recapitalized; that is, it funds itself, and the originating company can use the proceeds of the deal either internally or to buy something else.

But carve-outs are complex—strategically, legally, and operationally. They take time—often more than a year. And they don’t necessarily solve all the problems. A company can conduct a carve-out and still be left with the need to rationalize products and product lines and other costs within the surviving organization. For example, the originating company might need to rethink the size and structure of its corporate services, distribution arrangements, and other costs given that it has become a smaller organization.

If there’s an evident case for a carve-out, then, a company should set that aside while moving in parallel to capture the quicker gains from rationalization in the parts of the business that aren’t suited to carving out.

Click here to download the report.