Parmesh Bhaskaran

Chicago

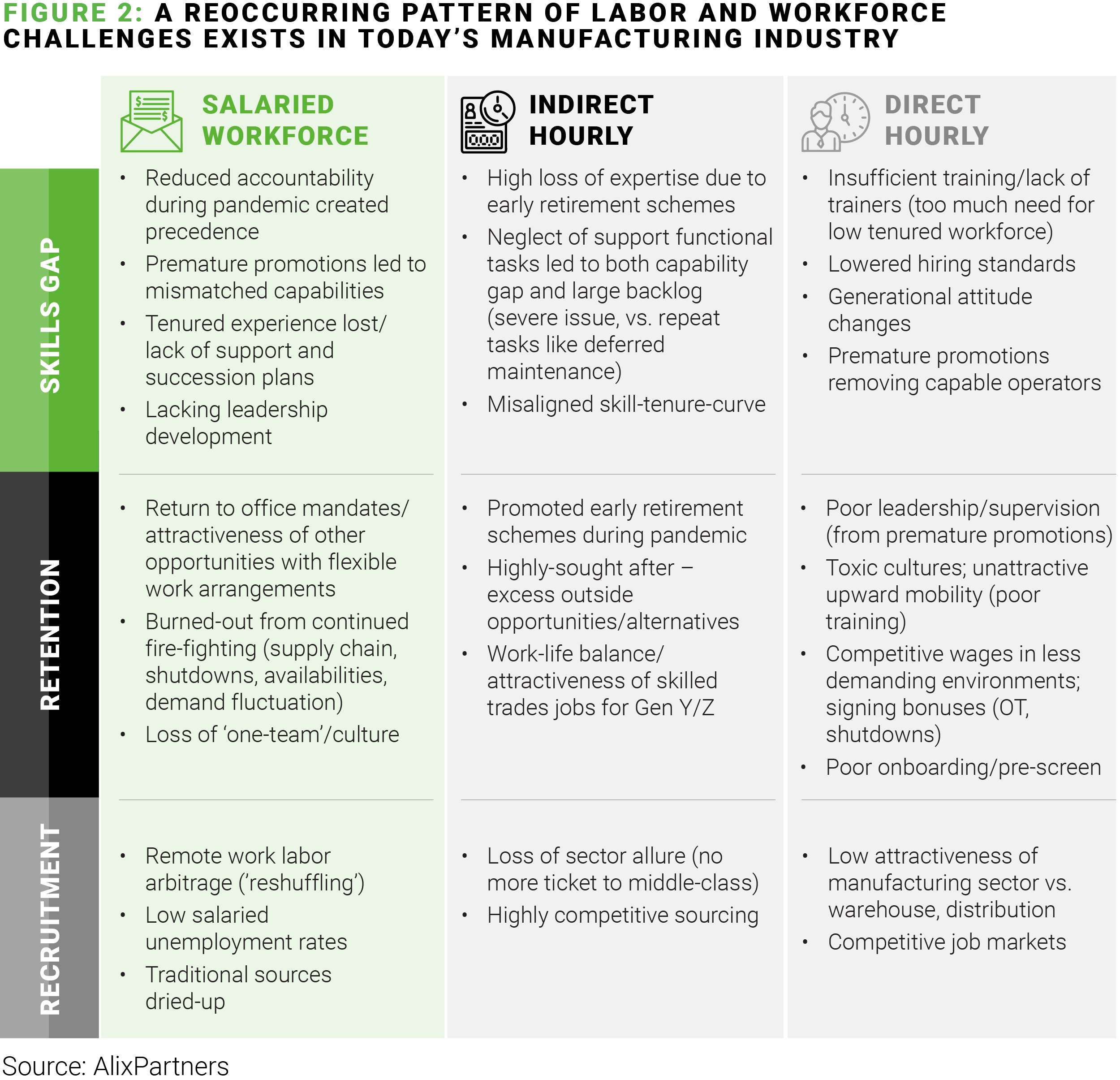

While the challenges around the hourly manufacturing workforce get most of the ink (particularly in light of the UAW strike), salaried workers are at an equally critical pivot point. The pandemic had a profound effect on companies far beyond the plant floor. The Great Resignation churned large swaths of the professional workforce. They moved on, citing low pay, lack of appreciation, and poor advancement opportunities.

The height of the Great Resignation appears to have crested as quitting slows to pre-pandemic levels. Its decline doesn’t come before exposing vulnerabilities related to salaried workforce management. Those vulnerabilities and a laundry list of associated problems will linger.

Right Person in the Wrong Chair

HR directors will be forgiven if they feel like they’ve been overseeing a game of musical chairs in recent years. Any predictability in managing the salaried ranks flew out the window as attrition numbers increased and the available talent pool dried up. The music has stopped, but the consequences of the game remain.

Addressing those consequences requires the attention of the entire management team and a realistic assessment of the state of play. Technology adoption, succession planning, people development, and communication strategies are part of the solution, but understanding the backdrop is necessary to properly route investments and resources.

In many cases, today’s salaried workforce is relatively unqualified, unfulfilled, and unhappy with leadership. A recent survey of roughly 2,500 workers conducted by The Muse had nearly three-quarters of respondents reporting their new role or company was very different from what they’d been led to believe; nearly half said they would try to get their old job back.

A separate study by The Conference Board, meanwhile, found less than half of respondents were satisfied with opportunities for advancement, including job training programs, recognition, and promotion policies—all areas over which employers have direct control.

How did we get here? In a word: Desperation.

The pandemic created a unique moment where many manufacturers experienced a sharp increase in demand at the same time as severe supply bottlenecks emerged. The number of qualified people equipped to manage the situation dwindled amid a wave of retirements and attrition. This turnover came amid heightened stress levels and long-lasting fire-fighting mode –This led to burnout, particularly among supply chain and operations personnel.

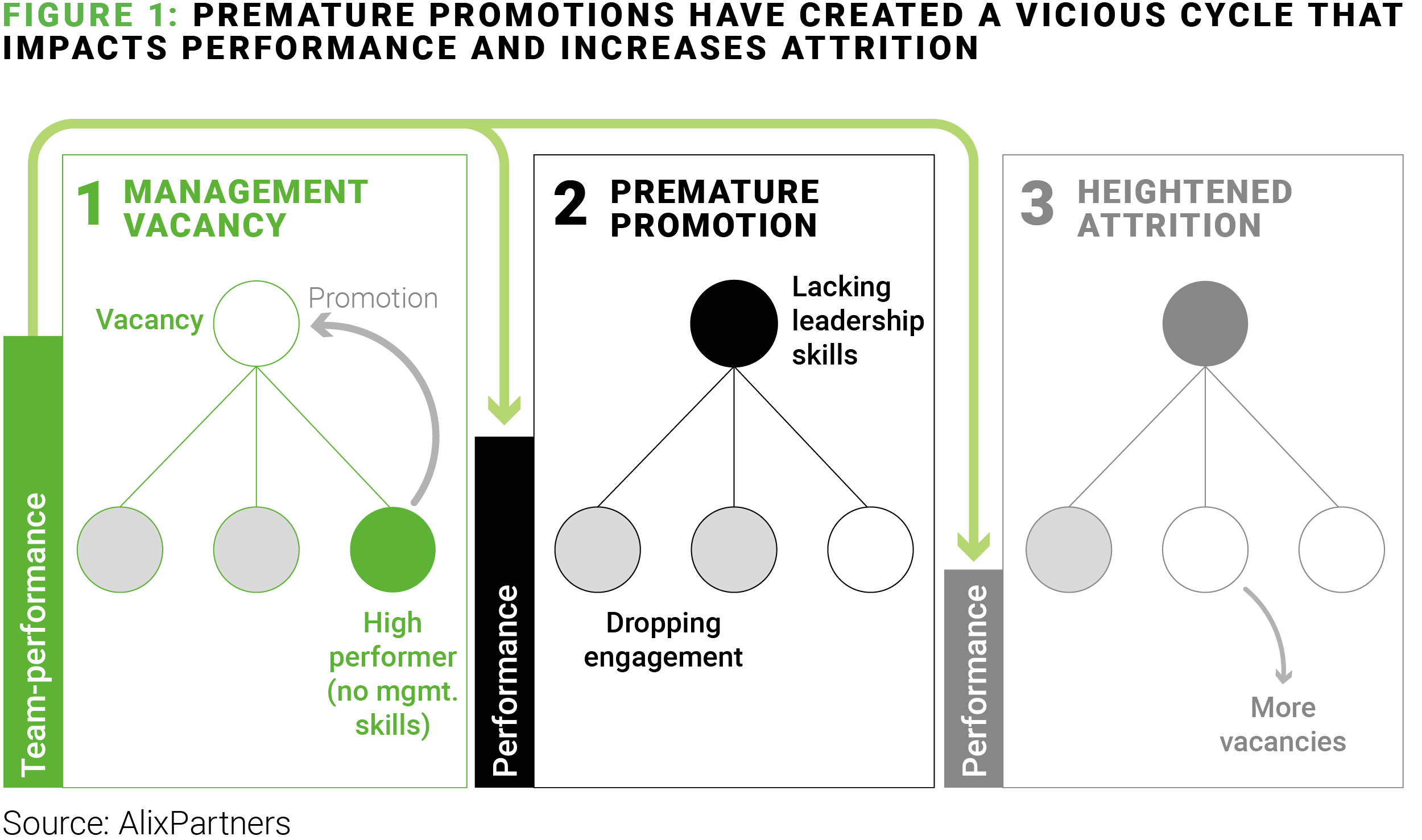

As a result, people were promoted prematurely or hired into roles even though they didn’t fit. This can have severe multiplier effects in relation to operations roles. We have witnessed endless cases of well-performing operators who lack leadership skills being promoted to supervisors or --even worse -- production managers without the training, coaching, or know-how to perform. This leads to a severe drop in performance and increased attrition among the ranks.

Fixing this problem starts by acknowledging that, no matter what industry you compete in, everyone is now operating in a knowledge economy. This is evident in multiple factors, including a wave of new work-from-home policies emerging during the pandemic and increased access to digital tools. Expectations for employers to clearly communicate roles and objectives, lay out a compelling career path, and offer flexibility in conditions and schedules.

When unaddressed, there is an erosion of accountability, which directly impacts the financial and operational health of the business. Companies also run the risk of experiencing an erosion of culture, which threatens morale levels, dents individual performance, and increases the likelihood of attrition.

We see the most immediate opportunity for improvement in the following areas:

We stated in our previous article that roughly 25% of the manufacturing workforce is over the age of 55, and a bulk of older employees haven’t shared enough information with those who will assume their roles once they leave. The days of apprenticeship seem to be a nostalgic pastime—we’d argue this is an essential practice needing revival.

How did this come about? A recent survey by the National Center for Middle Market notes that 46% of HR teams are operational—not strategic—and may not be capable of talent management and career development.

Proactive succession planning and clear job requirements do not solve the knowledge gap, but it does create a framework for proactive skill development, ensuring the most important skills are being transferred to up-and-coming performers at the right time and in the right format. The important first step is to identify the skills employees in critical roles need to learn. Once identified, use both internal and external resources to build capabilities.

Our routine visits to manufacturing companies convinced us too many key employees don’t know what is really expected of them. This leads to confusion, frustration, and, ultimately, underperformance. Employee survey firm Energage suggests the problem starts and ends with realistic expectations: when those aren’t set, employers are at a higher risk of losing talent. This is most prevalent in new hires, where there is often a mismatch between what was promised in the new job and reality.

Leaders set vision and direction for the company and rely on managers to provide structured coaching to support employees as they work day-to-day to carry those out. If job descriptions are vague or inaccurate, or progress is never monitored, the opportunities for growth and advancement become murky, and doubts about career progression creep in.

It is time for an overhaul of the way people are managed and departments interact. Most companies rarely improve or even catalog the core work processes that consume the organization’s most expensive salary resources. Most companies have enormous untapped opportunities to retool the organization with an eye on modernizing work processes, improving cross-functional coordination, and boosting productivity.

In the knowledge economy, technology plays an increasing role in the workplace, employees sometimes express fear. Still, digital tools need to be embraced as a way to simplify and standardize work.

Artificial intelligence and robotic process automation (RPA) are two leading concepts in digital transformation, but managers must also consider the entire suite of opportunities – from data management to cloud services and several other applications – in the effort to modernize. It is time to consider retiring manual Excel-based planning processes and replace them with robust, commercial ERPs to bridge the skills gap.

Rapid transition to integrated digital systems can also help reduce the risk of losing the knowledge of retiring employees. In a study by Express Employment, 78% of boomers said they had shared none, or less than half, of what they know with those who will take their place upon retirement.

Technology, in fact, can be an antidote to the major problem we’re seeing in the workplace related to burnout, particularly in manufacturing circles. Digital tools can relieve many of the headaches that humans experience when jumping from crisis to crisis.

A new plan for your salaried workforce

The Great Resignation left a good deal of chaos in its wake, putting people in the wrong roles across all the functions that keep manufacturing companies running. This jeopardizes more than just production activities—the entire top-to-bottom enterprise is affected.

The path to addressing this can be explained in four important steps:

Manufacturing may be changing, but people will always be a key ingredient. Optimizing their performance requires a new plan and dedicated investment. This is particularly true at this moment when reshoring is top of mind and supply chains remain challenging to navigate. Don’t let a salaried workforce that is intended to push the company forward be the factor that slows you down.

Other articles in this series

Next up in our series, we’ll cover overall strategies to address the biggest workforce challenges for manufacturers. What are proven operational and organizational considerations to undo what isn’t working? And how do you rebuild a performance culture?

Part 1 can be found here: Lessons from the factory floor Part 1: These labor pains aren’t temporary, Parmesh Bhaskaran, Steven Hilgendorf, Allen Merriman, Felix Pflaum, Stephen Smith, Chandan Singh (alixpartners.com)